The project placed first in the Architects Design Competition, organised by Transport Malta in collaboration with the Kamra tal-Periti, as part of

Prioritise the Pedestrian.

Why the transport question is about putting

AP in collaboration with the Institute for Climate Change and Sustainable Development of the University of Malta, has developed an urban design and mobility strategy for the village of Lija. It seeks in particular to address the domination of the urban environment by the car. The strategy is underpinned by background research primarily involving site observation and

What does the project set out to do?

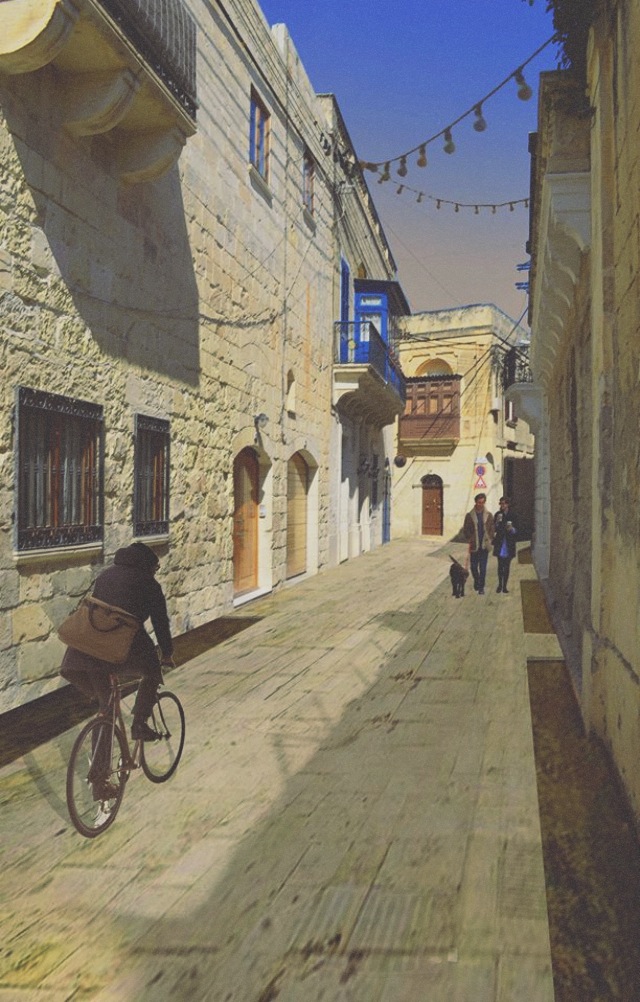

It’s fundamentally about putting people first –the urban environment is so remarkably dominated by the car – in terms of speed, noise and air pollution – and it’s something that we’ve come to take for granted – yet it has a huge impact on quality of life. It affects what we breathe, it affects our propensity to walk or cycle (and therefore our health too), it has a huge effect on the independence of children and the elderly in residential environments – it affects our ability to enjoy the very places we inhabit and to use the public realm for recreation or as a place for encounter

What makes Lija the ideal case study?

In the first place its small – that allowed us to get a good feel of things with the limited resources at our disposal. Its urban conservation area is characteristic of many other old, historical villages in Malta and faces huge traffic pressures. Rat-running through Lija means that when there is no traffic, cars speed through very narrow streets (and open doors literally get slammed shut) at great risk to pedestrians – when there is traffic there are half hour long queues of cars belching fumes into a

Strategy: what do we want to achieve?

The strategy is structured around three principal objectives with a

- Limit Traffic

In both quantity and speed, by re-routing to prevent through-traffic and by introducing measures to force cars to slow down, making the environment saferfor pedestrians . - Prioritise the Pedestrian

Creating more, safer and better pedestrian infrastructure by: limiting traffic and thus danger, noise and air pollution; by reconfiguring streets around the needs of pedestrians to encourage walking and actually designing the streetscape and introducing landscaping where possible to provide shade and to absorb some of the impacts (noise, air pollution) of vehicular traffic; and, in the long-term, by providing off-street parking that allows for street space to be freed up forother uses . - Enhance Public Space

By freeing up street space from the car clear pedestrian priority areas can be designated creating small pocket-piazzas and gardens for recreation, social interaction andcommunity activity .

Aren’t the same people putting pressure on space for use by the car, the same ones you will be needing to convince to change

Yes. The old core of Lija in particular presents a situation where people are living with these dangers all the time and are very much aware of them – but of course changing habits is never easy. We have presented the strategy to residents and those present were very positive. In the end we have to ask ourselves what kind of towns we want to inhabit and what small steps we can all take to make a change. Its argued that people in Malta resist walking and frankly the pedestrian environment is so poor that that’s hardly surprising – we can only encourage walking if we create environments that are safer, more comfortable and more stimulating to the senses of a human being walking at human speed. Of course cars and humans need to

What would you expect the social and environmental impacts of such a strategy to be? How’s everyday life going

Clearly there are many advantages in terms of a reduction in fuel emissions, improved visual, acoustic and air quality, increased safety, improvements in citizen health through opportunities for walking and cycling, encouraging more active lifestyles and giving opportunities for independence for the elderly and children in urban areas. There are also greater opportunities for urban recreation and social interaction and increased support of biodiversity in urban areas. Of course that might mean that people will need to learn to walk further to get to their front doors but we forget that that is the case in so many historic centres all over the world – we just also forget that the environment in those centres is attractive

Do you see this going forward?

The proposal represents perhaps a first comprehensive proposal for the gradual upgrading of mobility infrastructure in a Maltese village through a series of incremental interventions based on sound urban design and traffic calming knowledge. We think it’s valuable as a pilot project that can encourage other towns and villages to reclaim their streets from the car. Of course, strategies on paper are not enough. For us to engage with strategic national and European mobility and climate change objectives and make significant improvements to the overall quality of life of Malta’s citizens, we need to find models for action. Unfortunately the resources at the disposal of local councils are particularly scant. Still we are keen to see things develop – cities elsewhere have initiated change using soft measures and low-key infrastructure to test the suitability of interventions and to give people a taste of what urban space could be like if it didn’t prioritise the car all the time. We think that that might taste a bit better than much of the air we