Eski Shahar

New environments of exchange. A renovation strategy.

| Date | 2020 |

|---|---|

| Client | Confidential |

| Value | n.a. |

| Location | Tashkent, Uzbekistan |

The role of Malta as a bridge between East and West is not unlike that played by the cities that lie on the commercial routes called the Silk Roads. For millennia, these lines of passage were the bridges that linked Europe to the Pacific Ocean, from the Eastern shores of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea to the Himalayas. This network of pathways connected peoples and places together, like the world’s central nervous system. These cities were similar to Valletta in the way they were designed and consciously geared up to facilitate and organise trade. Like Valletta, as they developed and grew, they exchanged materials and goods and, above all, ideas. We therefore approached the project proposal for the regeneration of the Eski Shahar area in Tashkent as a dialogue with a 'sister city', a dialogue between

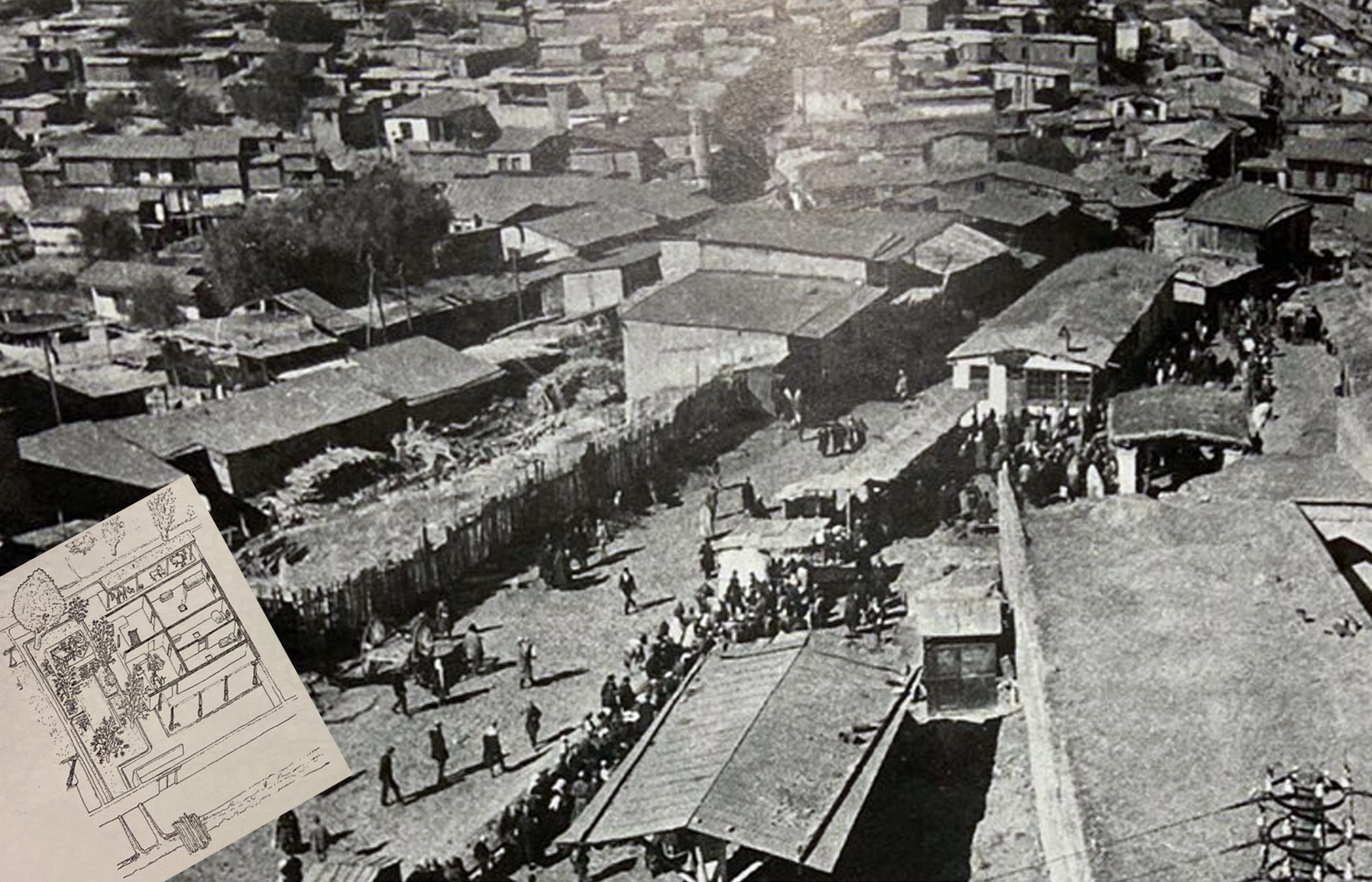

Initial studies focused on the historical, urban and cultural context, and on the traditional mahallah building typology in particular. For centuries, a characteristic oriental urban structure has developed with just a few open areas, mostly in front of bazaars and religious buildings. Narrow streets led through the mahallas to houses built around an inner courtyard; as a rule, their exterior wall is windowless. Access from the alley to the courtyard is via a corridor marked by repeated bends (just like the streets outside), so that even from the entrance door the view on the interior is protected. “Therein lies the fundamental difference from Western cities, whose shielding lays at the edge

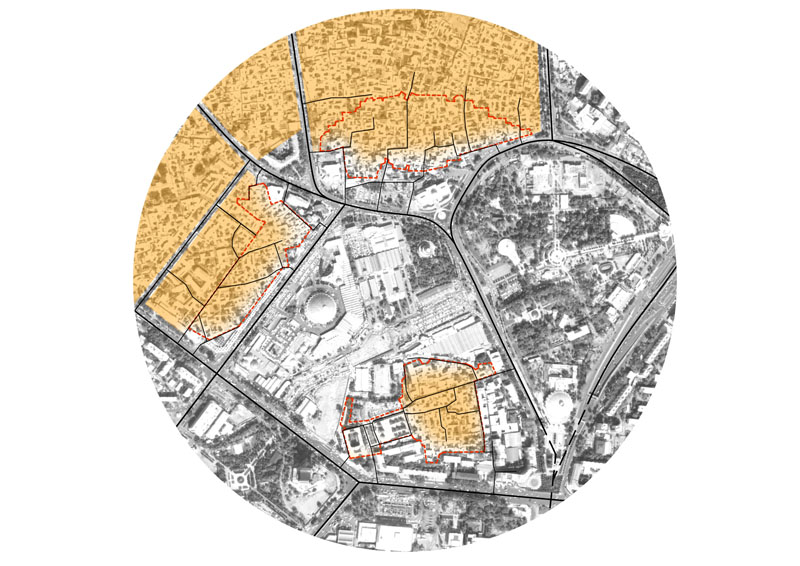

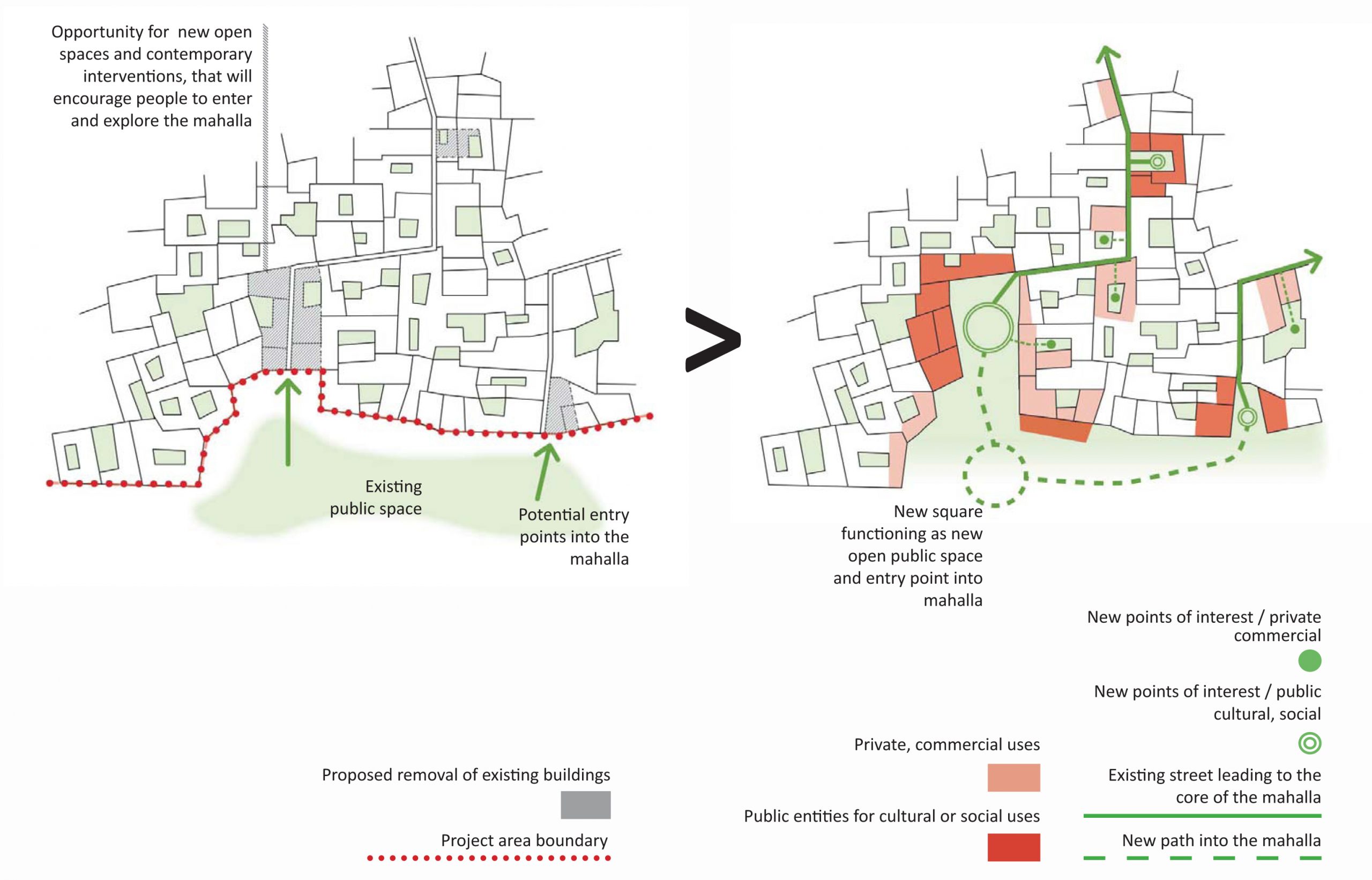

The Eski Shahar area today presents many of these vernacular characteristics, adjacent to contemporary interventions and main arterial roads which seem to be walled off in a very abrupt manner, causing a dramatic change of scale between the traditional urban fabric and the ‘new’ areas of development. These borders seem to be both the biggest challenge of the project and at the same time, the most promising opportunity for change, for the creation of new

Environment of exchange are in fact the one common theme that is constant throughout the history of Tashkent. Tashkent is built on intensive exchange – not just of goods, but of people, ideas, resistance, acceptance. The centrality of spaces for ‘exchanges’, both cultural and commercial, are historically part of the city's culture, as is obvious for example in Chorsu market. We see exchange as a transformative experience for actors, participants, and the environments that they and their actions sustain. Different forms of exchange co-exist side by side or are even intertwined with each other. Environments for exchange can develop organically, but they can also be orchestrated, directed, channeled, inspired, and stimulated in new directions, often through creative re-interpretations. Environments thus, in turn, rebound back and transform, modify, or re-inspire

The opportunity to address environments of exchange in Tashkent is therefore adopted as the strategic approach to identify regeneration potential. This implies not merely an architectural conservational model and restoration of an urban space, but rather exploiting this process as a stimulus for a sustained, on-going series of initiatives on a number of levels, primarily cultural, social and economic. It is people and society that make a place, not architectural conservation. This involves giving it a relevant present that is autonomous, self-sustaining and self-generative - not merely the

To give Tashkent a present is to give it a future. Its present (and future) cannot be a recreation (or more precisely, a re-enactment) of its past. That is the challenge - to conjure a present that has not

Main steps of the proposal development, which takes a truly sustainable stance from

- Identifying potential new uses, addressing the need for diversity and a more balanced mix of activities;

- Zooming in, at mahallahas' scale, and identifying a potential method of intervention which focuses on opportunities for interventions on the mahallas' borders, currently the most fragile areas;

- Zooming out again, at urban scale, and re-think connectivity, focusing on pedestrianisation as a strategy to improve movement within the mahallas and to/from their surroundings;

- Imagining the new environments of exchange

and their vibrant relationship with the existing urban context - how will people live in these new spaces?

In an effort to blend old and new, and to provide new spaces for exchanges on the borders between the two, new public spaces emerge and green areas connect them, while sensitive regeneration of the mahalla’s streets through restoration and upgrading of existing structures preserves the original spirit

We imagine the Tashkent of tomorrow through the re-interpretation of its environments

- a place with a high degree of social cohesion;

- a platform for cultural dialogue and diversity;

- a place for green, ecological and environmental regeneration;

- a hub for technological innovation;

- a place whose attractiveness will generate an engine of economic growth.

The economic benefits derived from regeneration are closely linked to the concept of livability, which is about creating places in which people will want to live and work. This brings investment and the development of skilled and higher paid work opportunities. This is dependent on the social, cultural and environmental improvement and wider processes

A successful regeneration programme will stem from the community that inhabits the location. It is the major stakeholder. If the regeneration programme works from a local perspective, it will automatically create attractiveness and visitors will flow in